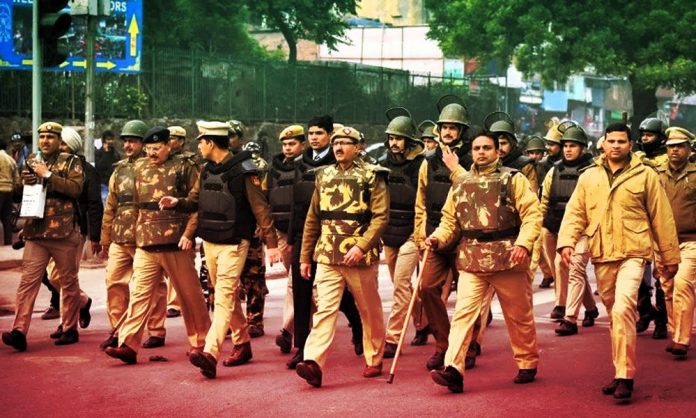

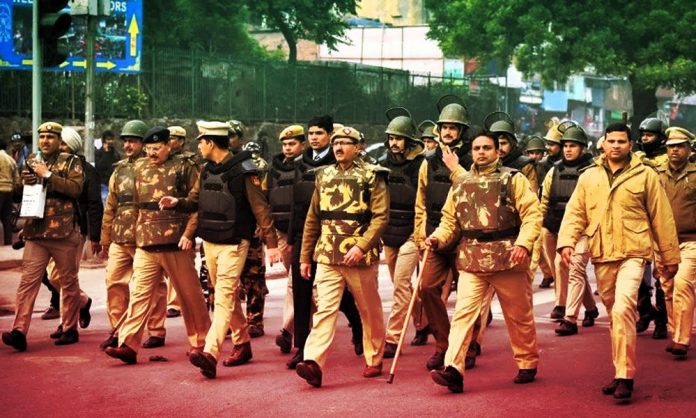

Amid the ongoing protests in Delhi against the CAA and NRC, Delhi’s Lieutenant Governor Anil Baijal, on 17th January 2020, vested the power to detain any person under the National Security Act, 1980 (hereinafter referred to as NSA) for the next three months, in the hands of the Delhi Police Commissioner. The sub-section (3) of Section 3 of NSA along with clause (c) of Section 2 of the Act gives power to the Lt. Governor to endow emergency detaining authority powers to the office of Delhi Police Commissioner. The act allows police to detain any person if it feels that the said person is a threat to national security. The person detained also need not be informed of the charges upon which he was detained for 10 days. The Delhi police will get such detention power with effect from January 19, 2020, to April 18, 2020.

However, the Delhi police has claimed that it is a routine order and is issued quarterly to maintain law and order in the country.

In August 2019, the Act was extended to the state of Jammu & Kashmir following the repeal of Article 370 of the Constitution of India, giving powers to armed forces in the area to detain a person on the ground of threat to national security.

The NSA was brought in by the Parliament of India in the year 1980. The Act provides for preventive detention in certain cases and matters connected therewith. The Act focuses on maintaining law and order in the country and provides for detention of individuals who try to impede the law and order situation of a state or country. The Act contains 18 sections and confers power on states and central government to detain any person in the presence of the following grounds:

India has had preventive detention laws dating back to the start of the colonial era. In the year 1818, Bengal Regulation III was passed which empowered the then government to arrest anyone in matters relating to defence or maintenance of public order without giving the person option of judicial proceedings. Again, after 100 years, the British government passed the Rowlatt Acts of 1919 that provided for the confinement of a suspect without trial.

After India got independence, the first Act that provided for preventive detention rule was enacted in the year 1950 during Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s government. The Act was called the Preventive Detention Act, 1950 . The NSA is enacted on similar lines with the 1950 Act. After the expiration of the Preventive Detention Act, 1950 on December 31, 1969, Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister, brought in the contentious MISA, 1971 (Maintenance of Internal Security Act), giving similar powers to the government. Though the MISA was abrogated by the Janata Party government in 1977, the successive government, headed by Indira Gandhi, brought in the NSA, 1980.

Section 8 of the Act states that when a person is detained in pursuance of a detention order made under the NSA, the authority, making the order shall as soon as may be, but ordinarily not later than 5 days, and 10 days from the date of detention, in case of exceptional circumstances, for reasons to be recorded in writing, communicate to him the grounds on which the order of arrest was made and shall afford him the earliest opportunity of representing himself against the order to the appropriate government.

However, as per sub section 2 of Section 8, the authority has the right to not disclose the facts which it deems to be against the public interest to disclose.

Section 9 of the Act states that:

Section 10 of the Act states that, save as otherwise expressly provided in this Act, in every case where the detention has been made under NSA, the appropriate government shall, within three weeks from the date on which the person was detained under the order, place before the Advisory Board commissioned by it under Section 9, the grounds on which the order has been made and the representation if made, by the person affected by the order and in case where the order has been made by an officer specified in sub section 3 of Section 3, also the report by such officer under sub section 4 of that Section.

Section 11 of the Act emphasises that the Advisory Board shall, after taking into account materials placed before it and after calling for further information as it may consider necessary from the appropriate government or from any person called for the purpose through the appropriate government or from the person concerned, and if, in any specific case, it considers it essential so to do or if the person concerned wishes to be heard, after hearing him in person, submit its report to the appropriate government within 7 weeks from the date on which the person concerned was detained.

It specifies that the report submitted by the Advisory Board to the appropriate government must separately specify the opinion of the Advisory Board as to whether or not there exists a sufficient cause for the detention of the person concerned.

It further states that when there is a difference of opinion among the members of the Advisory board, the majority opinion of such members shall be deemed to be the opinion of the Board.

The Section further reads that nothing in this Section shall entitle any person against whom a detention order has been made to appear by any legal practitioner in any matter related with the reference to the Advisory Board; and the proceedings of the Advisory Board and its report, excepting that part of the report where the opinion of the Advisory Board is specified, shall be confidential.

Section 13 of the NSA talks about the maximum period for which a person can be detained.

It states that the maximum period for which a person may be detained in pursuance of any detention order that has been made and confirmed is twelve months from the date of detention. However, the section contains a proviso which suggests that the appropriate government has the power to revoke or modify the detention order at any earlier time.

Section 14 talks about the revocation of a detention order. It states that, without prejudice to the provisions of Section 21 of the General Clauses Act, 1987 (10 of 1987), a detention order may be revoked or modified at any time:

The expiry of revocation of a detention order (hereinafter referred to as earlier detention order) shall not [whether such detention order has been made prior to or after the commencement of NSA (Amendment), 1984] bar the making of another detention order (hereinafter referred to as subsequent detention order) under Section 3 against the same person.

However, in a case where fresh facts have arisen after the revocation of the earlier detention order made against the person concerned, the maximum period for which such person may be detained in pursuance of the subsequent detention order shall, in no case extend beyond the expiry of a period of 12 months from the date on which such person was detained under earlier detention order.

Section 16 states that no suit or legal proceeding shall lie against the Central government or a State government, and no suit, prosecution or other legal proceedings shall lie against any person for any action taken in good faith or intended to be done in pursuance of the Act.

Normal Detention

Detention under NSA

When a person is detained normally, he has a right to be informed of the grounds of his detention.

Under the NSA, a person can be detained for 10 days without informing him of the charges against him.

A person who has been detained normally has a right to bail.

A person detained under the NSA does not have such right.

A person detained normally has the right to consult a lawyer.

A person detained under the NSA cannot take the help of the lawyers.

There have been many times when the provisions of the Act were used arbitrarily and without any reasonable cause. In January 2019, the BJP led Uttar Pradesh government arrested 3 persons under the NSA in connection with an alleged cow slaughter case in Bulandshahr. In December 2018, a journalist from Manipur named Kishore Chandra Wangkhem was detained for a period of 12 months under the NSA where he has posted an offensive post against the Chief Minister on Facebook. Experts opine that the governments sometimes use this Act as an extra-judicial power.

When a person is arrested normally, he or she has certain basic rights. Such rights include: the right to be informed of the reason for arrest and the right to bail. These rights are ensured by the various laws functioning in the country. Section 50 of the Criminal Procedure Code (Cr. PC) provides that an arrested person has the right to be informed of the grounds of such arrest, and the right to bail. Likewise, Section 56 and 76 of the Cr. PC also enumerates that an arrested person shall be produced before a court within 24 hours of arrest. Furthermore, Article 22(1) of the Constitution of India guarantees that an arrested person cannot be denied the right to consult, and to be defended by a lawyer of his choice.

However, such basic rights are not available to a person who has been detained under the provisions of NSA. A person has no right to know about the grounds of his detention for up to 5 days and in certain circumstances, not later than 10 days. While providing the reason for arrest, the government has the power to reserve information which it thinks would go against the public interest if disclosed. The arrested person has no right to seek the aid of any lawyer in any matter concerned with the proceedings before an Advisory Board, which has been constituted by the government to deal with the NSA cases.

Moreover, the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), which collects data related to crime in India, does not include cases under the NSA as no FIRs are registered in this regard. Thus, it is impossible to have an idea about the exact number of detentions that have been made under this Act.

The Act, though, provides for maintaining law and order in the country, lacks reasonableness. Certain provisions of the Act are arbitrary and there is no recourse available against such provisions. The Act also ignores the basic rights of the arrested persons that are available to them if they are arrested normally.

Students of Lawsikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skill.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Follow us on Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more amazing legal content.